FREDERICK (FRED) ANDREW GAMMELL JACOBS

INTRODUCTION

After finding some old military records relating to my maternal grandfather, I thought I would try to find out what happened to him during the Great War. When I was about ten years old I recall talking with Fred about the war and remember his story of burning down the hospital tent (see text below). That said, like many of his generation, Fred probably found talking about the Great War difficult and upsetting.

The Battle of Arras (9th April to 16th May 1917)

The Leger Holidays pamphlet “Walking Arras” states: “The end of the Battle of the Somme in November 1916 marked in many ways the end of that spirit of optimism, particularly in Britain, which believed that war could be over in the Summer and Autumn of 1916. A new word had entered military strategy, attrition; there was now a belief that war could not be finished within a short period and that the warring nations would have to consider new tactics to avoid the heavy losses of 1916”.

The plan agreed by the Allies in early 1917 was that the main attack should be carried out by the French, in the area between Soissons and Reims, with the British in a supportive role, attacking the Germans in the Arras sector. The British (and Dominion troops) attack started on 9th April, with a major success being the capture of Vimy Ridge by the Canadians. The Germans rushed troops in to reinforce their defences and prevented further gains by the British.

The French attack (The Nivelle offensive) was a disaster, leading to severe losses and the mutiny of soldiers. This meant the British were forced to continue their attacks in the Arras sector to keep the pressure off the French Army.

The Battle of Arras is relatively unknown now. The British casualty figures were shocking and illustrated the fierceness of the fighting:

Arras – Duration 39 days – Casualties 159,000 – Daily Rate 4,076.

Somme – Duration 141 days – Casualties 415,000 – Daily Rate 2,943.

What Probably Happened to Fred at Arras. (As told by Fred with acknowledgments to “the War History of the Queen’s Westminster Rifles 1914-1918” by Major Henriques).

The War History states: “On April 7th, the regiment moved to Achicourt in the Arras sector. Four days later, the 169th Infantry Brigade, which included the Queen’s Westminster Rifles (QWR), moved up to the Cojeul Switch, east-north-east of Neuville Vitasse, in Brigade reserve. Battalion Headquarters were established in a dugout in Telegraph Lane, on the south-western slope of Telegraph Hill. The 169th Infantry Brigade was now ordered to make good the whole of Hill 90, which commanded Wancourt and Héninel, as soon as the 30th division, had captured the Hindenburg line. At the end of April 12th, the 2nd London’s, (a fellow regiment in the 169th Brigade), had established themselves on the Wancourt Tower Ridge, about 1000 yards south-east of Héninel and were in touch with the 14th Division, which had reached the western edge of Wancourt. At 10 p.m. on the 13th, an order was received, warning that an attack would be launched from the Wancourt Ridge, with the Queen’s Victoria Rifles on the right and the QWR on the left. The objectives were, firstly, a ridge, about 1000 yards in advance of the Tower Ridge, from which the attack was to start, and secondly, the capture of the village of Chérisy. No previous reconnaissances of the ground over which they were to attack had been possible and there was no time for any proper explanation to them of what they were to do. In fact, little more could be done than to give the dispositions for the attack and the general line of the advance on objectives which none of the attacking troops had ever seen”.

I’ve been asked what was it like to be in the trenches in April 1917. It was a terrible time and I don’t like to think about it too much but I’ll try to explain. In the QWR regiment, we were all volunteers, we’d trained together and we all trusted and relied on one another; we were proud to be serving our King and Country together. We shared the anxiety of not knowing if, or when, we would ever see our homes and families again. I was certainly scared and we all knew the severe casualties that our mates in the QWR had suffered at Gommecourt in July 1916. We too ran the risk of being killed or maimed every day.

We lived in foul conditions; the smell of rotting flesh from dead men and horses was always there. We were plagued by rats and lice, we couldn’t wash ourselves or our clothes properly and we were cold and damp most of the time. The food was bland; we lived on tea, bully beef and hard biscuits, although sometimes we were able to get our hands on a bottle of wine! Noise from guns firing, shells exploding, people shouting and animals neighing and braying was ever present.

Despite all that, it was dreadfully tedious; most of the time there was nothing to do but to sit around with mates, smoking, drinking tea and wondering what was to become of us. By the evening of April 13th everyone in the regiment was exhausted, even though we hadn’t been in action yet. For the last three days I doubt if any of us had more than one hour’s sleep.

Before the attack I thought that I’d be very lucky to survive for long, but I was here in the line and I was going to serve my country and make my family proud of me, whatever happened. Our officers were good men and we trusted them to lead us bravely. I remember Lieutenant Orr, my Company Commander, talking to the men and encouraging them. He said that he was proud to command such brave and loyal men. The brandy just before the attack helped to steady us all somewhat!

Ten minutes before our artillery barrage was due to begin the Germans started a heavy bombardment near Wancourt Tower, close to the QWR position, on our regiments left flank, too near me for comfort! The noise from the enemy bombardment was incredible and shell fragments were flying everywhere. Our guns soon opened up and the noise was just horrendous. I’ve never since heard such noise nor do I want to again.

At zero hour (5.30 a.m. on April 14th), the attacking waves advanced. ‘A’ Company on the right, ‘B’ Company on the left, followed by ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies respectively, I was in ‘C’ Company which formed the second wave of the attack. I can remember the first wave taking terrible casualties with intense machine gunfire and shelling. It was an inferno, and a living hell!

Eventually we were ordered forward, the noise reached a crescendo, men were shouting and screaming, there was smoke and dust everywhere. I‘d run just about 150 yards across exposed ground when I was hit by what felt like a train. I found myself lying on the ground, feeling tired and weak. I remember wondering if this was what it is like to die. My next memory was of waking up in the Casualty Clearing Hospital that was about 10 miles behind the front line.

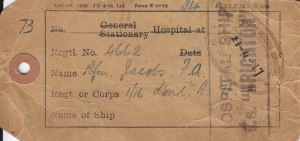

Fred’s Field Medical Card shows that he was taken by the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) 96th Field Ambulance (attached to the 30th Division) from the Regimental Aid Post to the Casualty Clearing Station. He was very fortunate in being found by the RAMC and they obviously saved his life. The 30th Division was fighting on the right of the QWR and the 56th Division.

I was given leave and on 9th July 1917, married Maud Causton. I learned later that Maud used to travel up to London to read the early newspaper editions to see if I was a casualty.

I often thought of my fallen comrades and wondered why I had survived.

Frederick (usually known as Fred), was born on 23rd March 1892, and he and Maud Causton were married on 9th July 1917. They had two children; Edna Maud Jacobs (now Mundy) was born on 5th February 1921 and Geoffrey Frederick Jacobs was born on 3rd July 1925. Fred died on 13th May 1982.

Fred was a rifleman in the Queen’s Westminster Rifles (1/16th Battalion London Regiment) Number 4662 – 16BLR – Dog Tag 551837. Fred was most likely wounded at Wancourt on 14th April 1917. Geoffrey Jacobs recounts that Fred told him that he was wounded at Vimy Ridge, which is only a few miles from the Wancourt / Héninel sector. Fred had a severe wound caused by a British shell splinter – lower abdominal left wall (groin). The shell splinter was kept in a case for many years but was lost after Fred died.

Fred, who by this time had been in France since 9th December 1916, was taken back to England on the hospital ship SS Brighton on 21st April 1917. Disembarked at Dover, he was taken to Bolton Hospital by ambulance train. In 1917, the hospital was called Bolton General (now the Royal Bolton Hospital) and wards L and M were used for wounded soldiers. After recovering from his injuries, Fred joined the Royal Flying Corps (now The Royal Air Force), for the rest of the war.

Fred’s military records and those of many of his compatriots were destroyed in a bombing raid in 1940 and this story of his experiences in the Great War has been reconstructed from various reliable primary sources. Fred’s loyal service to his King and country did not go unrewarded; he received both the British Victory Medal and the British War Medal.

APPENDIX ONE

THE QUEEN’S WESTMINSTER RIFLES

QWR on 14th April 1917

Queen’s Westminster Rifles 1/16th Battalion London Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel Shoolbred)

Comprised

4 companies (A B C D and HQ staff)

Company A

3 Platoons and the HQ: Approx 150 men (Captain Agate)

1 Platoon: (4 sections) 25-40 men (Lieutenant and Sergeant)

1 Section: 8-12 men under a NCO

Company B (Lieutenant Yeates)

Company C (Lieutenant Orr)

Company D (2nd Lieutenant Palmer)

COMMAND STRUCTURE: The Battle of Arras (9th April to 16th May 1917)

Third Army (General Allenby)

VII Corps (Lieutenant General Snow): 5 Divisions

56th (1st London) Territorial Division formed February 1916: Divisional Commander (Major General Hull)

3 Infantry Brigades: 167th Brigade, 168th Brigade and 169th Brigade

169th Brigade (Brigadier General Coke)

Comprised

2nd London’s (1/2nd Battalion London Royal Fusilers)

London Rifle Brigade (1/5th Battalion London Regiment)

Queen’s Victoria Rifles (1/9th Battalion London Regiment)

Queen’s Westminster Rifles (1/16th Battalion London Regiment)

Various other Divisional troops

APPENDIX TWO

Acknowledgments and sources:

I would like to thank the following for their help in writing this history of Fred. It started out as a three page summary and just grew and grew. Every time I thought I had finished I would find out more about Fred.

My late grandfather, Fred Jacobs and my late grandmother, Maud Jacobs, both of whom I fondly remember.

My mother, Edna Mundy, for finding the old documents about her father but not before I had booked a Battlefield Tour to the Somme where I had thought that Fred had been wounded! I had to re-book when I looked at the documents!

My late father, William Mundy, who was also in the QWR but not until a few years before the Second World War.

My late uncle, Geoffrey Jacobs, for information about Fred, especially the details about Bolton Hospital.

My uncles, Frank and Anthony Mundy, for their encouragement in writing Fred’s family history.

My brother, Christopher Mundy, for his encouragement and the suggestion that part of the story be written: “As told by Fred”.

My brother, Robert (Bob) Mundy, for his constructive suggestions and for greatly improving (or improving greatly) my grammar and punctuation – and not least, helping to proof read the story!!!

Mrs Karina Jackson, for her encouragement and help in obtaining Fred’s birth, marriage and death certificates.

The two tour guides (Peter Williams & Vic Piuk), drivers and the entire group, on the Leger Holidays “Walking Arras Tour” in June 2010.

Sources consulted include:

Books and pamphlets:

Cheerful Sacrifice. The Battle of Arras 1917. Nicholls.

The Battle for Vimy Ridge – 1917. Sheldon & Cave.

The South-Eastern & Chatham Railway in the 1914-1918 War. Gould.

The War History of The Queens’s Westminster’s Rifles 1914-1918. Major Henriques.

Walking Arras. Paul Reed.

Walking Arras. Leger Holidays a pamphlet for a walking tour of Arras battlefields in June 2010.

Picture Credits:

The view from Hill 90, from the German position in 1917 towards Héninel. http://www.webmatters.net/france/ww1_arras_VII.htm

Frederick Andrew Jacobs. The Mundy family collection.

Fred’s Hospital Ticket, Wound Description and Field Medical Card. The Mundy family collection

SS Brighton, Fred’s Hospital Ship in April 1917. http://www.simplonpc.co.uk/SR_LBSC1.html

Fred’s Dog Tag.. The Mundy family collection.

All other pictures taken by the author in June 2010.

© Andrew Mundy. 1st Edition August 2010 (Privately published). This 2nd Edition was published in May 2015 on a Word Press blog post with slight amendments and corrections.